Improving Text Generation for Product Description by Label Error Correction

Improving Text Generation for Product Description by Label Error Correction

Abstract

Text generation serves as a crucial technique for producing accurate and usable product descriptions from product titles. The primary challenge in product description generation for online e-commerce applications lies in achieving sufficient usability rates for generated text. Current online deployment standards require usability rates exceeding 99%. Traditional model-centric approaches remain constrained by training dataset quality. To address this limitation, we propose a data-centric methodology that enhances generation model usability rates from 88.0% to 99.2%. Our approach helps in building models using LLMs (large language models) annotation results and constructing datasets to obtain better results than LLMs API. The methodology significantly streamlines human labeling efforts by reducing annotation tasks to binary classification decisions, thereby accelerating labeling speed. In summary, our solution achieves a tenfold reduction in labeling time while attaining 99.2% accuracy suitable for online deployment.

1. Introduction

In e-commerce, product descriptions can attract shoppers and improve sales. However, manually writing effective product descriptions is highly time-consuming. Text generation \cite{zhang2022survey,prabhumoye2020exploring} technologies play a crucial role in this range of applications.

In recent years, developments in deep learning (DL) have brought breakthroughs in text generation. Sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) models utilize encoder-decoder transformers \cite{vaswani2017attention} to achieve greater flexibility. Prominent examples of such models include T5 and BART \cite{raffel2020exploring,lewis2020bart}. In this paper, we employ the T5 model to perform our data-centric experiments.

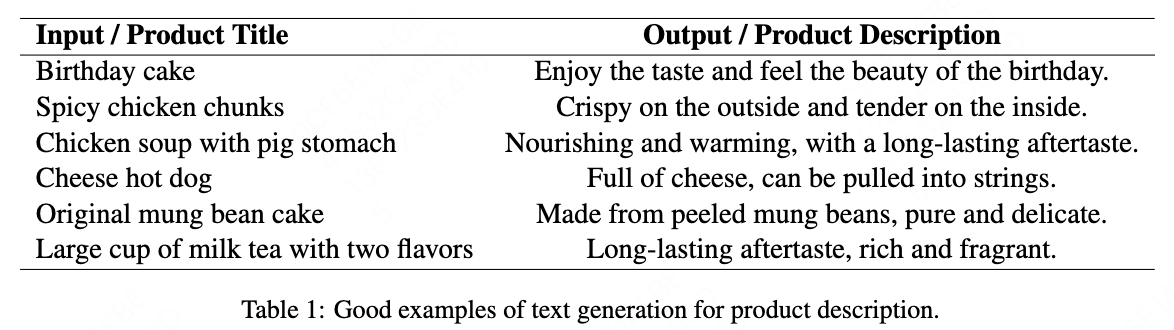

Text generation has an input or a source sequence $X$ and an output or a target sequence $Y$ to be generated. In our product description generation tasks, $X$ is the product title and $Y$ is the product description. The examples are shown in Table \cite{table1}.

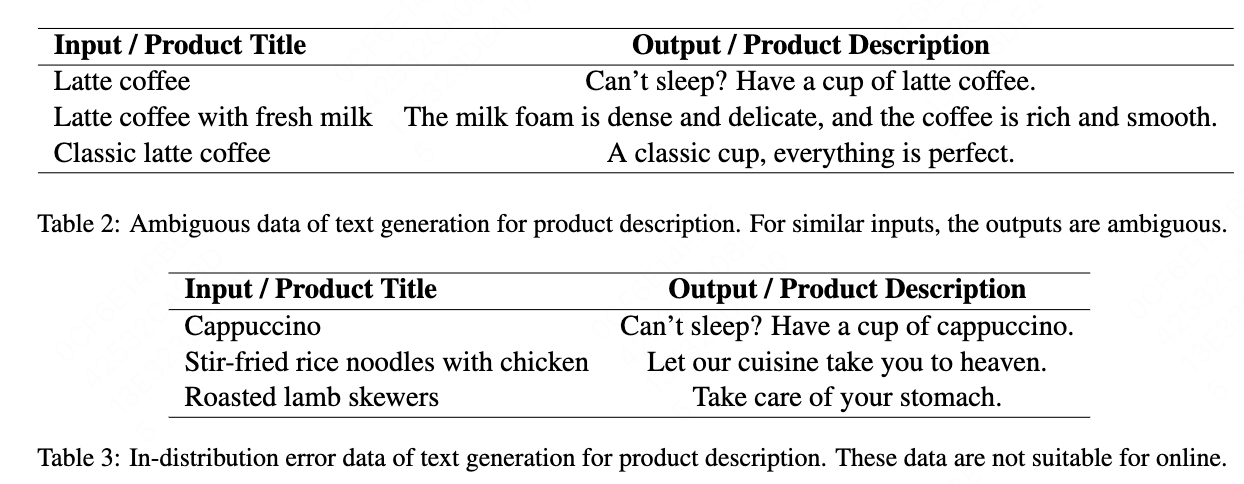

In online applications, we mainly face low accuracy or low availability rate problems: Model-centric method is limited by the quality of the training dataset. The generation results’ accuracy needs to be above 99\% as too many erroneous descriptions would result in poor user experience. Our initial availability rate was only 88\% after initially constructing the training dataset by querying ChatGPT \cite{ouyang2022training,openai2023gpt}. The reason for the low accuracy is that there exists a significant amount of erroneous data in the training dataset that is unsuitable for display. For instance, while a product is titled ‘fish-flavored shredded pork’, the corresponding description in the training dataset states “this dish is spicy.” Consequently, such product descriptions may not be suitable for non-spicy “fish-flavored shredded pork” products. More examples are shown in Table \cite{table2} and \cite{table3}.

The speed of manual annotation is a critical challenge. In our scenario, 80\% of the time is spent on data labeling. For example, annotating 100,000 data points currently takes 2 weeks. If we adopt the baseline method requiring five people to label the same data for quality assurance, the data preparation would require 10 weeks to complete. Conversely, by reducing labeling time by half, this process could be completed in just 1 week.

To solve the aforementioned problems, we designed the Self-Predict and Choose method to correct errors in ambiguous data, and developed the Self-Search and Remove method to address in-distribution errors, while also overcoming issues with manual annotation errors.

The contributions of our paper are:

(1) We propose a data-centric method for improving text generation models’ accuracy and success rates. Our method achieves a 99.2\% success rate in our product description generation task being deployed online.

(2) Our method focuses on minimizing labeling effort by identifying ambiguous and erroneous data in training datasets. It reduces labeling time by tenfold compared to the baseline approach of repeatedly checking all training data. For all annotation stages, labelers only need to make two-class selections - the most efficient and reliable annotation format.

(3) Our method can be applied to various text generation tasks, achieving accuracy rates above 99\%. It also has broad applicability to deep learning applications using human-annotated datasets.

2. Method

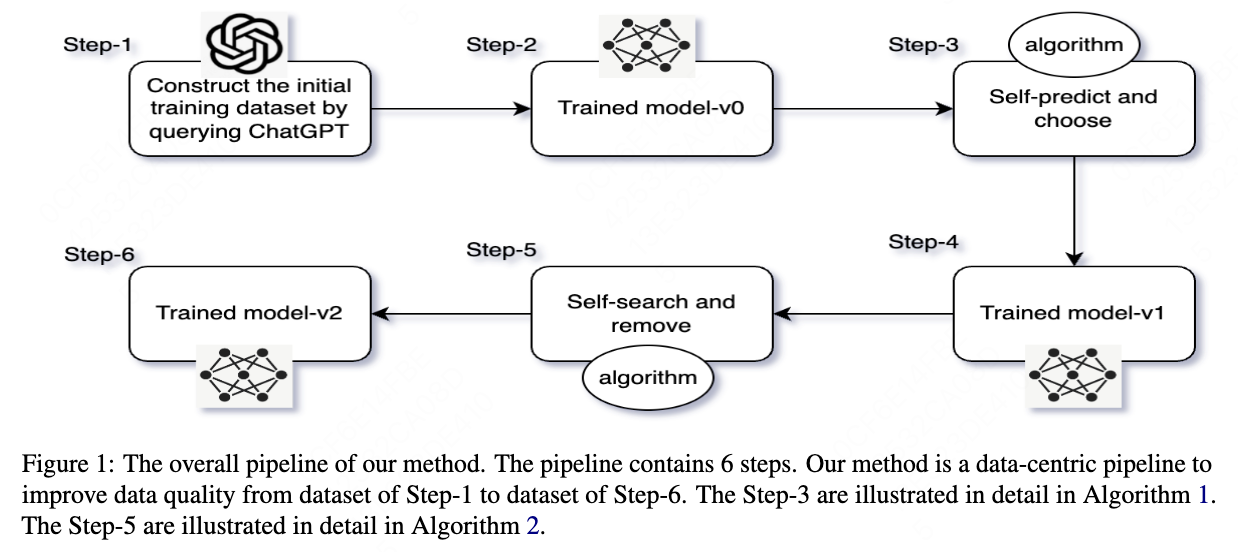

The whole pipeline is shown in Figure \cite{fig1}. In this paper, we adopt the T5 \cite{raffel2020exploring} model to conduct our experiments. The pipeline contains six steps. In this section, we illustrate the details of each step and how the algorithms work. In the discussion section, we explain the motivation behind designing these steps.

2.1 Initial Training Dataset Construction

This section corresponding to the Step-1 in Figure \cite{fig1}. We collect our initial training dataset by querying ChatGPT. Each prompt is formed by concatenating a product title. We ask ChatGPT to write descriptions for the products. We tried to add some product attributes as prompt, but most of the ChatGPT’s results do not relate to the product attributes. Table \cite{table1}, Table \cite{table2} and Table \cite{table3} shows the prompt examples and the ChatGPT’s results. Our T5 \cite{raffel2020exploring} model trained on this initial dataset gets 88\% available rate, under human evaluation.

2.2 Out-of-distribution Ambiguous Data

Out-of-distribution ambiguous data is observed in our training dataset. The examples are shown in Table \cite{table2}. These data has similar inputs, the outputs are very different. Some of them are error data.

2.3 In-distribution Error Data

In-distribution error data is observed in our training dataset. The examples are shown in Table \cite{table3}. These data and its similar data are error data. These error data cannot be found by using Algorithm \cite{alg1}.

2.4 Self-Predict and Choose

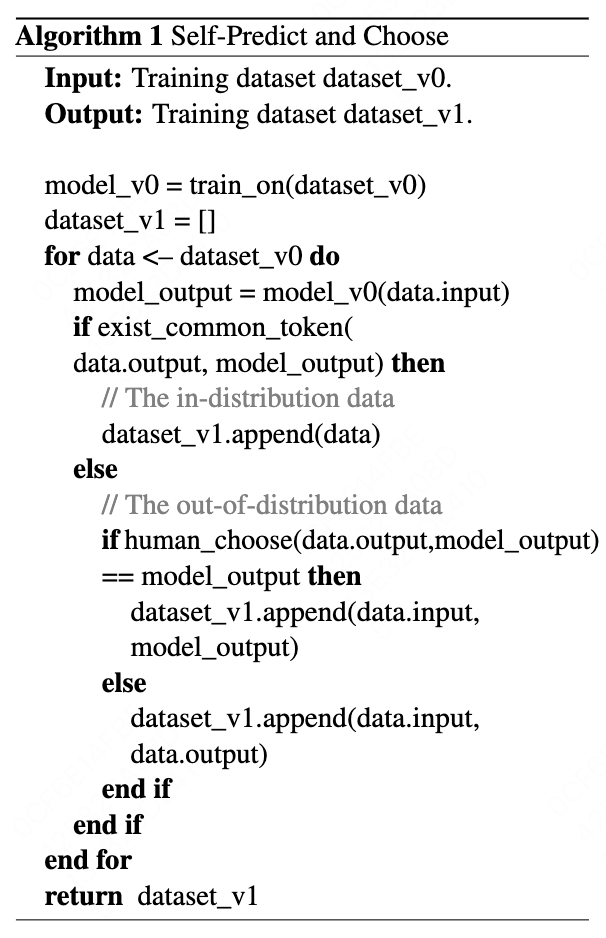

This section corresponding to the Step-2 in Figure \cite{fig1}. The algorithm detail is shown in Algorithm \cite{alg1}.

Because we have observed that there are many ambiguous data in the training dataset. So we design this algorithm is to correct error data in the ambiguous data by predicting itself and human re-labeling. We train the seq2seq model until the dev loss no longer decreases.

In Algorithm \cite{alg1}, we have the model_v0 trained on the dataset of last step. Then we use model_v0 to predict outputs for the inputs of training dataset. If the model output is significantly different from the output of the same input in the training dataset, then we manually choose a better output for the input. Then we get the corrected dataset_v1. In this paper, if the model output and training data’s output do not have common token, we identify they are significantly different and not similar.

2.5 Self-Search and Remove

This section corresponding to the Step-5 in Figure \cite{fig1}. The algorithm detail is shown in Algorithm \cite{alg2}.

Because we have observed that there are many extremely error data in the training dataset. These extremely error data are in-distribution with the training dataset. So these data cannot be fixed by Self-Predict and Choose method of Algorithm \cite{alg1}. Algorithm \cite{alg1} is mainly to find the out-of-distribution data.

So we design this algorithm is to fix these data in training dataset by manually annotating the seed dataset. The seed dataset is randomly sampled from the training dataset. We try to retrieve the error data by the smallest number of seed data.

In Algorithm \cite{alg2}, we have the model_v1 trained on the dataset of last step. Then we use model_v1 to predict results for the seed dataset and manually find the error data and right data in seed dataset. Then we use this human feedback: We search in the training dataset by querying each error data of seed dataset. Then we find all the most similar data to the error data in training dataset and remove them from the training dataset. Then we get the cleaned dataset_v2. In this paper, if the error data and training data have the most amount of common tokens, we identify they are the most similar.

We also tested embedding-based method for the similar search. We extract embedding from the seq2seq model’s encoder for the similarity calculation. We did not observe any significant improvement for embedding-based search.

We design the removing operation in this algorithm. Because it makes annotation errors tolerable. We observe that, removing some correct data due to annotation errors does not have a significant impact on the final result.

3. Experiment

In this section, we illustrate the dataset size, model parameters and experimental results.

3.1 Evaluation

3.1.1 Available Rate

In this paper, we do not use BLEU to evaluate the generation results. In our scenario, our goal is to determine whether the generated text is available. We use human annotation to compute the available rate:

\[Acc = N_{good} / N_{total}\]where $N_{good}$ is the available generated text number and $N_{total}$ is the total texts that are human annotated.

3.1.2 Online Dataset

The online dataset is all the data in the application database. It contains 500,000,000 data. Other datasets are all sampled from this dataset. It is the dataset for the final model inference.

3.1.3 Evaluation Dataset

We sample 5,000 data from all the 500,000,000 data online for manual evaluation for each step. We evaluate the model performance for the models of Step-2, Step-4, Step-6.

3.1.4 Training Dataset

The initial training dataset is prepared by querying ChatGPT. Considering the resource cost, we have prepared 300,000 data.

3.1.5 Seed Dataset

Seed dataset is sampled from the training dataset for Algorithm \cite{alg2}. Based on how many error data we want to retrieve, the approximate size of seed dataset can be calculated as:

\[N_{seed} = \frac{(1 - Acc_{training}) * N_{training} / K_{search} }{ (1 - Acc_{training})}\]Then we get:

\[N_{seed} = N_{training} / K_{search}\]where $N_{seed}$ is the seed dataset size. $Acc_{training}$ is the available rate. $K_{search}$ is the average searched texts amount by each data of seed dataset.

3.1.6 Dev Dataset

We split 1:20 from the training dataset as the dev dataset. The dev dataset is used to select the optimal model.

3.2 Experimental Setup

Both the T5 \cite{raffel2020exploring} encoder and decoder have 8 transformer layers. The hidden size is 768 and the attention head number is 12. We compared T5 and GPT-2\cite{radford2019language} on the same dataset and ultimately chose T5.

3.3 Experimental Results

The experiment results is shown in Table \cite{table5}. Our goal is to achieve the standard for online deployment, so we manually evaluate the available rate of test dataset as the evaluation metric. The T5 \cite{raffel2020exploring} model trained on the initial training dataset by querying ChatGPT gets 88.0\% available rate. After we use our Self-Predict and Choose method, the accuracy is improved to 95.1\%. After we use our Self-Search and Remove method. The accuracy is ultimately improved to 99.2\%. The Self-Predict and Choose method step improve the accuracy to 95.1\%, which means we have a good foundation to perform error data removing in the next steps. Then the Self-Search and Remove method can consume fewer annotation resources.

4. Discussion

In this section, we discuss the motivation why we design our method and the advantage of our method.

4.1 Motivation

In this sub-section we illustrate why we design the algorithms.

We design Algorithm \cite{alg1} because we found a certain amount of ambiguous data in dataset_v0. There are multiple significantly different outputs for similar inputs. Therefore, using the method of Self-Predict can find these ambiguous data efficiently.

We design Algorithm \cite{alg2} because we found data with error labels in dataset_v1. Data with error labels have similar inputs. Also, error data have similar common patterns. Therefore, using the method of Self-Search can find the error data in dataset_v1 efficiently.

4.2 Baseline Solutions

In this sub-section, we discuss other possible solutions to this problem. In summary, the essence of each method is the comparison of labeling efficiency.

4.2.1 Product attributes for input

In addition to product title as input, we have tried putting the product attributes like product type and product tags into the prompts, but we do not observe some improvement of text quality and diversity by ChatGPT.

4.2.2 Choose from multiple outputs

If we query ChatGPT and get multiple results for each input, we can manually choose the best output. The disadvantage is that it consumes multiples of the labelling time.

4.2.3 Labeling each data by multiple times

To ensure the quality of the dataset, we can label each data by multiple times and get all the correct data. The disadvantage is that it also consumes multiples of the labelling time.

4.3 The Advantage Of Our Method

In this section, we illustrate the advantages of our method compared to the baseline methods mentioned above.

First, we aim to resolve ambiguous data in the initial training dataset. If we were to label the entire training dataset to eliminate ambiguous data, the labeling effort would be approximately 10 times greater than our method requires. Our Self-Predict and Choose method avoids searching through all data in the training dataset and narrows the scope requiring labeling.

Second, manual labeling errors might lead to incorrect removal of data from the training dataset. In Step-5, we address both error removal and manual annotation inaccuracies. Our designed algorithm ensures model performance remains unaffected even if some valid data is mistakenly removed, as we observe that while some valid data might be eliminated, erroneous data has a significantly greater negative impact.

4.4 The Pipeline Steps Order

The sequence of steps in our pipeline is crucial for achieving optimal results. This section explains the rationale behind our specific ordering.

We position Step-3 before Step-5 because:

(1) Out-of-distribution data correction must precede in-distribution error removal.

(2) Step-3’s ambiguous data processing directly impacts Step-5’s error quantity.

(3) More ambiguous data identified in Step-3 leads to: Increased erroneous data requiring processing in Step-5.

5. Related Work

5.1 Transformer-based Models

The pre-trained model based on Transformer \cite{vaswani2017attention} has greatly improved the performance in various NLP tasks. The learning objectives include masked language modeling (MLM) and causal language modeling (CLM). MLM-based Language Models include BERT \cite{devlin2018bert}, ROBERTA \cite{liu2019roberta}. CLM-based Language Models include the GPT series works \cite{radford2018improving,radford2019language,brown2020language} and other decoder-only transformer models \cite{keskar2019ctrl}.

5.2 Seq2Seq Models

The sequence to sequence models\cite{sutskever2014sequence} use encoder-decoder transformer \cite{vaswani2017attention} for better model flexibility. The seq2seq model is widely used in the field of text generation \cite{luong2014addressing,bahdanau2014neural}. We adopt Seq2Seq models implement our text generation tasks. The most representative models of this type include T5 \cite{raffel2020exploring} and BART \cite{lewis2020bart}. In this paper, we adopt the T5 model to conduct our experiments. We compared T5 and GPT-2\cite{radford2019language} on the same dataset and ultimately chose T5.

5.3 Product Description Generation

There are many works in this area. \cite{chen2019towards} adds personalized features to solve the personalized product description task. \cite{zhang2019automatic} focuses on designing the pattern controlled decoder to ensure the quality of the description. \cite{wang2017statistical} propose a system framework for product description generation. \cite{chan2019stick} focuses on the model-centric method to solve this problem. In our paper, we focus more on achieve the standard for online deployment by efficient human participation.

5.4 Data-Centric Method

Data-centric \cite{zha2023data,openai2023gpt,ouyang2022training,batini2009methodologies,ratner2016data} AI focuses a greater emphasis on enhancing the quality and quantity of the data with the model relatively fixed. Data-centric representative tasks includes data collection, data labeling, data augmentation. Data-centric AI methods are categorized into automation and collaboration depending on whether human participation is needed. Our method need human participation and focuses on the label-again way to improve the quality and quantity of dataset.

5.5 Label Error Detection

Label error detection\cite{wang2022detecting,yu2023delving,hendrycks2016baseline,yu2022predicting,yue2022ctrl,song2022learning,natarajan2013learning} and confident learning \cite{northcutt2021confidentlearning,kuan2022labelquality} is the core of our method. Based on the idea of noisy data detection, we design algorithms to make the most efficient use of annotation manpower and achieve sufficient accuracy.

6. Conclusion

The challenges in product description generation for online e-commerce applications lie in the availability rate of generated text and the time consumption required for training dataset annotation. While model-centric approaches are constrained by training dataset quality, we propose a data-centric method that achieves 99.2\% accuracy, meeting the standard for online deployment. Our solution additionally reduces annotation time by approximately tenfold.

References

@inproceedings{lewis2020bart,

title={BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension},

author={Lewis, Mike and Liu, Yinhan and Goyal, Naman and Ghazvininejad, Marjan and Mohamed, Abdelrahman and Levy, Omer and Stoyanov, Veselin and Zettlemoyer, Luke},

booktitle={Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics},

pages={7871--7880},

year={2020}

}

@inproceedings{chan2019stick,

title={Stick to the facts: Learning towards a fidelity-oriented e-commerce product description generation},

author={Chan, Zhangming and Chen, Xiuying and Wang, Yongliang and Li, Juntao and Zhang, Zhiqiang and Gai, Kun and Zhao, Dongyan and Yan, Rui},

booktitle={Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP)},

pages={4959--4968},

year={2019}

}

@inproceedings{chen2019towards,

title={Towards knowledge-based personalized product description generation in e-commerce},

author={Chen, Qibin and Lin, Junyang and Zhang, Yichang and Yang, Hongxia and Zhou, Jingren and Tang, Jie},

booktitle={Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery \& Data Mining},

pages={3040--3050},

year={2019}

}

@article{vaswani2017attention,

title={Attention is all you need},

author={Vaswani, Ashish and Shazeer, Noam and Parmar, Niki and Uszkoreit, Jakob and Jones, Llion and Gomez, Aidan N and Kaiser, {\L}ukasz and Polosukhin, Illia},

journal={Advances in neural information processing systems},

volume={30},

year={2017}

}

@article{raffel2020exploring,

title={Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer},

author={Raffel, Colin and Shazeer, Noam and Roberts, Adam and Lee, Katherine and Narang, Sharan and Matena, Michael and Zhou, Yanqi and Li, Wei and Liu, Peter J},

journal={The Journal of Machine Learning Research},

volume={21},

number={1},

pages={5485--5551},

year={2020},

publisher={JMLRORG}

}

@article{ouyang2022training,

title={Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback},

author={Ouyang, Long and Wu, Jeffrey and Jiang, Xu and Almeida, Diogo and Wainwright, Carroll and Mishkin, Pamela and Zhang, Chong and Agarwal, Sandhini and Slama, Katarina and Ray, Alex and others},

journal={Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems},

volume={35},

pages={27730--27744},

year={2022}

}

@article{guo2021comprehensive,

title={A Comprehensive Comparison of Pre-training Language Models},

author={Guo, Tong},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.11483},

year={2021}

}

@article{devlin2018bert,

title={Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding},

author={Devlin, Jacob and Chang, Ming-Wei and Lee, Kenton and Toutanova, Kristina},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805},

year={2018}

}

@article{liu2019roberta,

title={Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach},

author={Liu, Yinhan and Ott, Myle and Goyal, Naman and Du, Jingfei and Joshi, Mandar and Chen, Danqi and Levy, Omer and Lewis, Mike and Zettlemoyer, Luke and Stoyanov, Veselin},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692},

year={2019}

}

@inproceedings{zhang2019automatic,

title={Automatic generation of pattern-controlled product description in e-commerce},

author={Zhang, Tao and Zhang, Jin and Huo, Chengfu and Ren, Weijun},

booktitle={The World Wide Web Conference},

pages={2355--2365},

year={2019}

}

@article{brown2020language,

title={Language models are few-shot learners},

author={Brown, Tom and Mann, Benjamin and Ryder, Nick and Subbiah, Melanie and Kaplan, Jared D and Dhariwal, Prafulla and Neelakantan, Arvind and Shyam, Pranav and Sastry, Girish and Askell, Amanda and others},

journal={Advances in neural information processing systems},

volume={33},

pages={1877--1901},

year={2020}

}

@article{radford2018improving,

title={Improving language understanding by generative pre-training},

author={Radford, Alec and Narasimhan, Karthik and Salimans, Tim and Sutskever, Ilya and others},

year={2018},

publisher={OpenAI}

}

@article{radford2019language,

title={Language models are unsupervised multitask learners},

author={Radford, Alec and Wu, Jeffrey and Child, Rewon and Luan, David and Amodei, Dario and Sutskever, Ilya and others},

journal={OpenAI blog},

volume={1},

number={8},

pages={9},

year={2019}

}

@inproceedings{wang2017statistical,

title={A statistical framework for product description generation},

author={Wang, Jinpeng and Hou, Yutai and Liu, Jing and Cao, Yunbo and Lin, Chin-Yew},

booktitle={Proceedings of the Eighth International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 2: Short Papers)},

pages={187--192},

year={2017}

}

@article{keskar2019ctrl,

title={Ctrl: A conditional transformer language model for controllable generation},

author={Keskar, Nitish Shirish and McCann, Bryan and Varshney, Lav R and Xiong, Caiming and Socher, Richard},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.05858},

year={2019}

}

@article{zhang2022survey,

title={A survey of controllable text generation using transformer-based pre-trained language models},

author={Zhang, Hanqing and Song, Haolin and Li, Shaoyu and Zhou, Ming and Song, Dawei},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.05337},

year={2022}

}

@article{prabhumoye2020exploring,

title={Exploring controllable text generation techniques},

author={Prabhumoye, Shrimai and Black, Alan W and Salakhutdinov, Ruslan},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.01822},

year={2020}

}

@article{zha2023data,

title={Data-centric artificial intelligence: A survey},

author={Zha, Daochen and Bhat, Zaid Pervaiz and Lai, Kwei-Herng and Yang, Fan and Jiang, Zhimeng and Zhong, Shaochen and Hu, Xia},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.10158},

year={2023}

}

@article{sutskever2014sequence,

title={Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks},

author={Sutskever, Ilya and Vinyals, Oriol and Le, Quoc V},

journal={Advances in neural information processing systems},

volume={27},

year={2014}

}

@article{luong2014addressing,

title={Addressing the rare word problem in neural machine translation},

author={Luong, Minh-Thang and Sutskever, Ilya and Le, Quoc V and Vinyals, Oriol and Zaremba, Wojciech},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.8206},

year={2014}

}

@article{bahdanau2014neural,

title={Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate},

author={Bahdanau, Dzmitry and Cho, Kyunghyun and Bengio, Yoshua},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473},

year={2014}

}

@article{wang2022detecting,

title={Detecting label errors in token classification data},

author={Wang, Wei-Chen and Mueller, Jonas},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.03920},

year={2022}

}

@article{yu2023delving,

title={Delving into Noisy Label Detection with Clean Data},

author={Yu, Chenglin and Ma, Xinsong and Liu, Weiwei},

year={2023}

}

@article{northcutt2021confidentlearning,

title={Confident Learning: Estimating Uncertainty in Dataset Labels},

author={Curtis G. Northcutt and Lu Jiang and Isaac L. Chuang},

journal={Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research (JAIR)},

volume={70},

pages={1373--1411},

year={2021}

}

@inproceedings{kuan2022labelquality,

title={Model-agnostic label quality scoring to detect real-world label errors},

author={Kuan, Johnson and Mueller, Jonas},

booktitle={ICML DataPerf Workshop},

year={2022}

}

@article{openai2023gpt,

title={GPT-4 technical report},

author={OpenAI, R},

journal={arXiv},

pages={2303--08774},

year={2023}

}

@inproceedings{hendrycks2016baseline,

title={A Baseline for Detecting Misclassified and Out-of-Distribution Examples in Neural Networks},

author={Hendrycks, Dan and Gimpel, Kevin},

booktitle={International Conference on Learning Representations},

year={2016}

}

@inproceedings{yu2022predicting,

title={Predicting out-of-distribution error with the projection norm},

author={Yu, Yaodong and Yang, Zitong and Wei, Alexander and Ma, Yi and Steinhardt, Jacob},

booktitle={International Conference on Machine Learning},

pages={25721--25746},

year={2022},

organization={PMLR}

}

@article{yue2022ctrl,

title={Ctrl: Clustering training losses for label error detection},

author={Yue, Chang and Jha, Niraj K},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.08464},

year={2022}

}

@article{song2022learning,

title={Learning from noisy labels with deep neural networks: A survey},

author={Song, Hwanjun and Kim, Minseok and Park, Dongmin and Shin, Yooju and Lee, Jae-Gil},

journal={IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems},

year={2022},

publisher={IEEE}

}

@article{natarajan2013learning,

title={Learning with noisy labels},

author={Natarajan, Nagarajan and Dhillon, Inderjit S and Ravikumar, Pradeep K and Tewari, Ambuj},

journal={Advances in neural information processing systems},

volume={26},

year={2013}

}

@article{batini2009methodologies,

title={Methodologies for data quality assessment and improvement},

author={Batini, Carlo and Cappiello, Cinzia and Francalanci, Chiara and Maurino, Andrea},

journal={ACM computing surveys (CSUR)},

volume={41},

number={3},

pages={1--52},

year={2009},

publisher={ACM New York, NY, USA}

}

@article{ratner2016data,

title={Data programming: Creating large training sets, quickly},

author={Ratner, Alexander J and De Sa, Christopher M and Wu, Sen and Selsam, Daniel and R{\'e}, Christopher},

journal={Advances in neural information processing systems},

volume={29},

year={2016}

}